When unscrupulous merchants placed cheap, lower-quality tobacco products in the empty wooden boxes of higher-end products to sell, tobacco manufacturers in the late 19th century faced a problem. Since all tobacco products essentially looked the same, how could they differentiate their plug and twist tobacco products from the competition? Manufacturers needed to find a solution to this frustrating problem.

By 1880 Americans began using products that were factory-made, cheaper and standardized. Examples are soups, soaps, canned goods, cereals, and safety razors. Advertising became an important means of luring consumers with something other than the lowest possible price.

Tobacco manufacturers dove head-first into this new practice of branding and gave their products unique names and symbols to create brand loyalty among consumers. After a brief flirtation with paper tags, tin tags became an important means of branding most plug tobacco products. In the beginning, these small pieces of tin of varying sizes – about the size of a quarter – were embossed with the name of the brand and cut into various shapes sometimes corresponding to the brand name. In the case of plug tobacco, the tin tag would have two small prongs that would be bent down and pushed into the plug to secure it. Later, as technology advanced, manufacturers used lithographed tags, with bright colors and custom images.

Tobacco tags quickly became highly collectable whether the collector used tobacco or not. More than 12,000 plug brands were registered between 1870 and the 1920s, many with their own distinctive tin tags. By 1886 a collectors club counted among its members individuals from across the United States and published a newsletter allowing collectors to buy, sell and trade by mail.

In the plug tobacco industry of the 1890s, a widely-used and successful marketing tactic was the first nationwide premium system. Tobacco manufacturers redeemed their tags for gifts, many publishing catalogs offering prizes from candy to pocketknives to grandfather clocks.

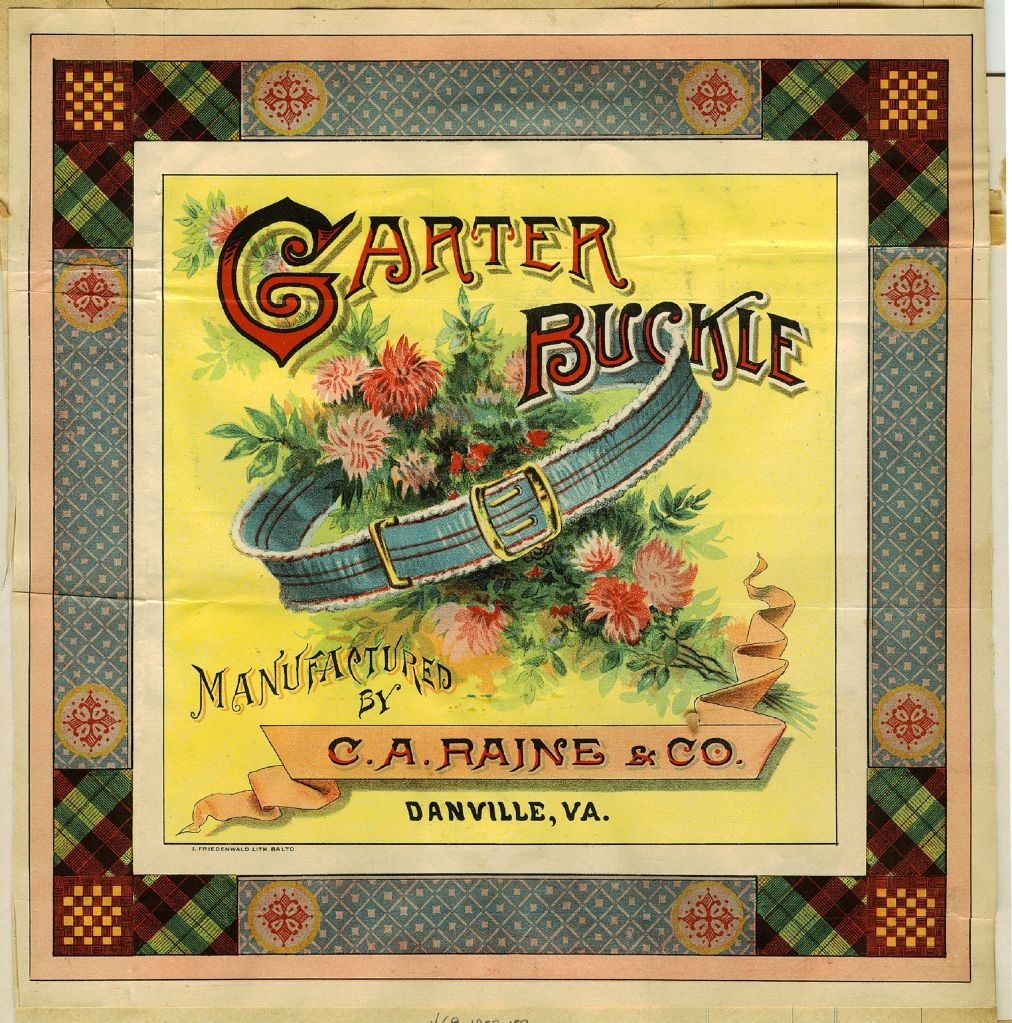

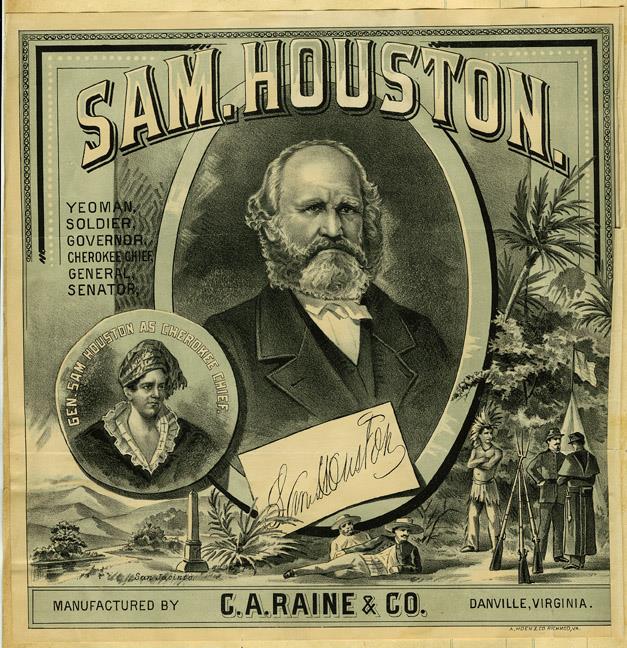

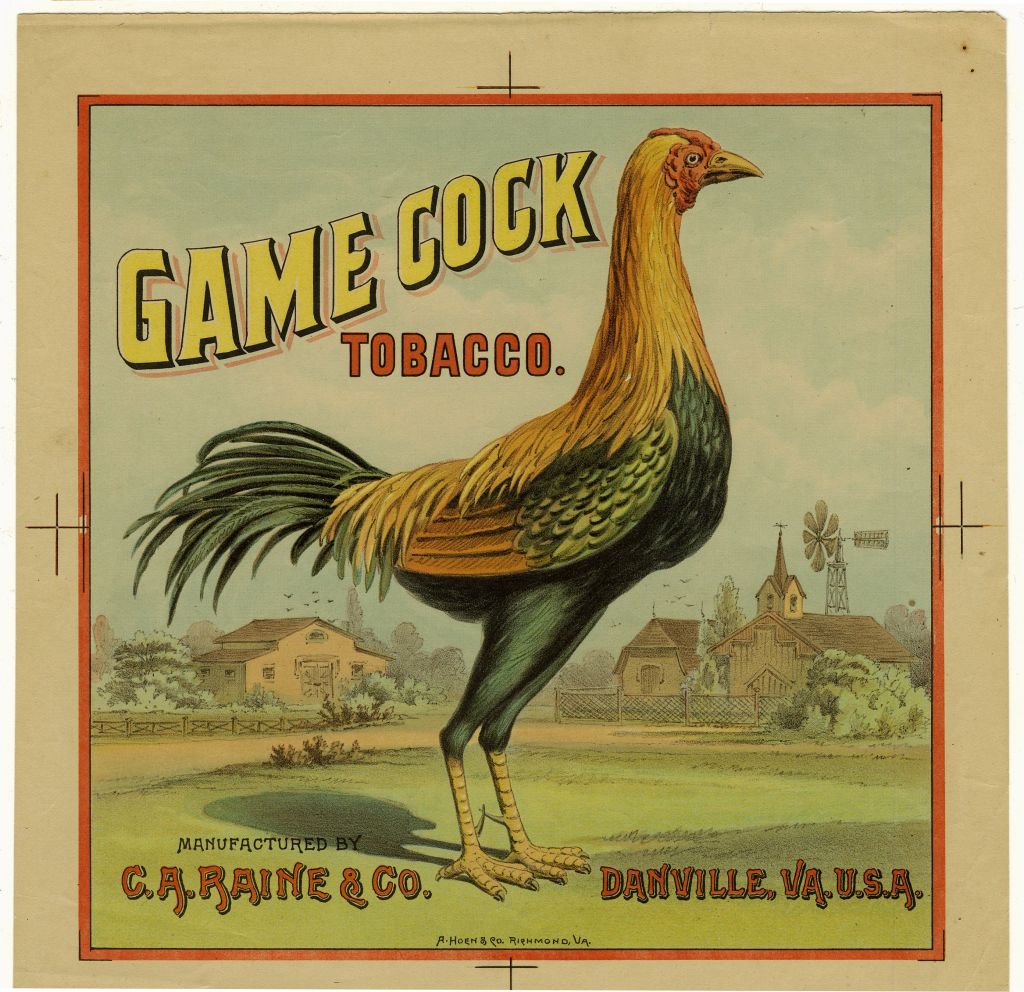

C.A. Raine & Co. was no exception to the rule and many tags used by the company survive and are highly collectible. Since it was one of the older tobacco manufacturers, examples of Raine tags can be found in both embossed and lithographed examples, often in the same brand. An example is “Garter Buckle” which must have had a fairly long production run or at least straddled the change from embossed to lithographed tags.

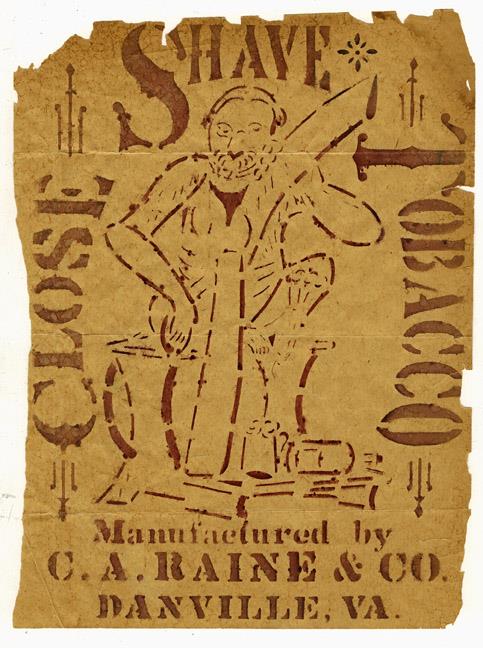

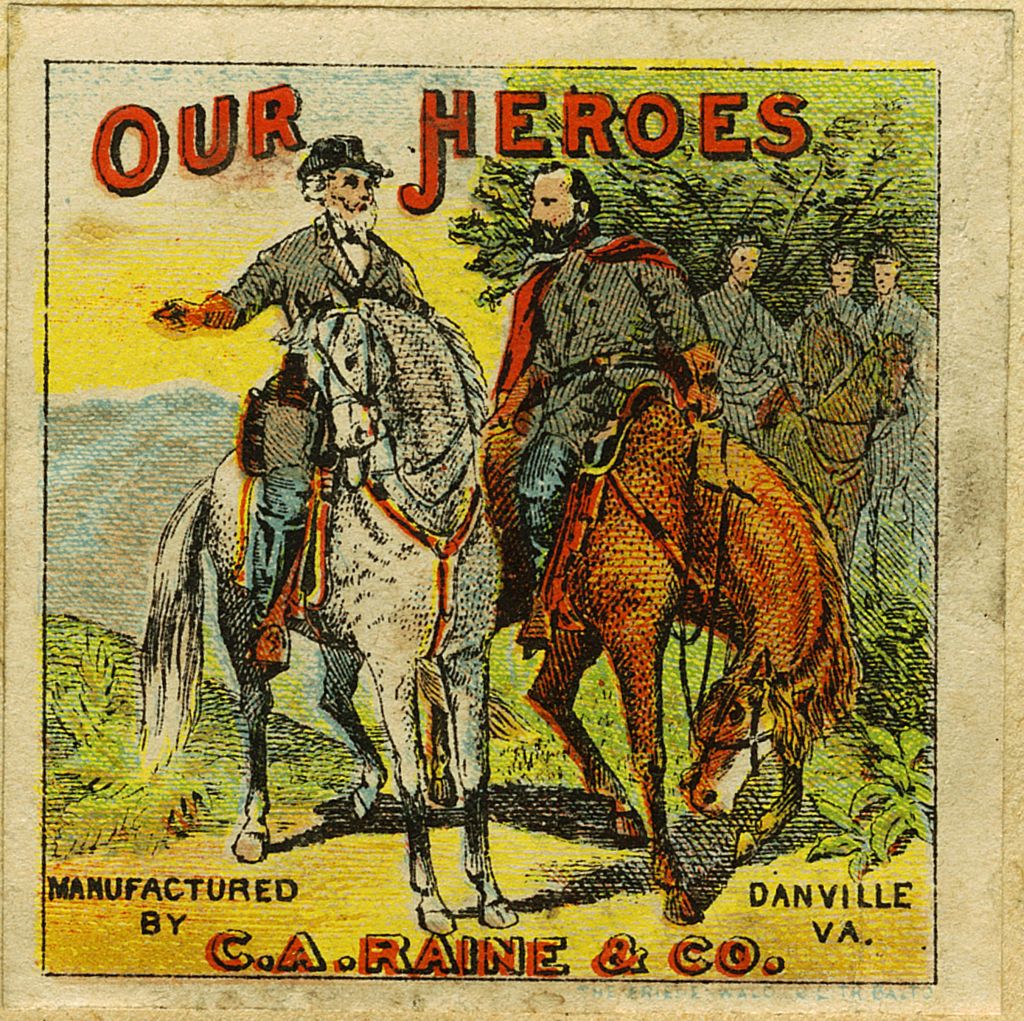

As far as I know, some Raine brand name tags only exist as embossed tags. These are “Our Heroes,” “Buck Eye,” and “XX Grade L.C.” To the best of my knowledge, other brands like “Raine,” “Lager,” “Close Shave,” and “Helen Wilson” only exist as lithographed tags. Other Raine brands like “Dickens Twist” do not appear to have any surviving tags, paper or tin.

Tin tags were a cost effective solution for manufacturers to distinguish their tobacco products from the competition. An expert on the American tobacco industry, Gerard H. Petrone, wrote that tobacco tags were “a relatively inexpensive but highly effective means of advertising. They fit into the thriftiest corporate budgets, no matter how large or small the firm.”

Sadly, tobacco tin tags began to disappear with the advent of wrappers made of materials like cellophane. The popularity of these tags has diminished but there are collectors who still appreciate their value and the window they provide into the 19th-century tobacco business.

Sources:

Kluger, Richard. Ashes to Ashes: America’s Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris. Vintage Books. 1996. Print

Petrone, Gerard S. Tobacco Advertising: The Great Seduction. Schiffer. 1996. Print.

Note: Thanks to Michael Wagoner of Winston-Salem, tobacciana collector and expert on tobacco tags, for sharing his knowledge.